You open Ads Console, see a “good” ACOS, and still feel like the account is leaking cash.

That usually means you are optimizing to a proxy metric while your actual unit economics (COGS, fees, coupons, returns, inventory costs) quietly changed. Amazon PPC profit tracking is the fix - not another dashboard for vanity ROAS, but a system that answers one question per SKU: after every fee and ad dollar, did we make money?

Why Amazon PPC profit tracking breaks when you rely on ACOS

ACOS is useful, but it is not profit. ACOS only compares ad spend to attributed ad sales. It ignores your margin structure and it ignores non-ad sales that ads often create.

Two SKUs can sit at 25% ACOS and behave like opposites. A high-margin product with stable fees can print profit at 25%. A low-margin product with aggressive coupons, high FBA fees, and frequent returns can lose money at 25%.

It also depends on your goal. If you are launching, you might accept short-term losses for ranking and review velocity, then pull ACOS down after. If you are in a mature category and already own your organic positions, the same ACOS target is wasteful. Profit tracking forces you to state the intent of the spend and measure it correctly.

Start with the only number that matters: break-even ACOS

Break-even ACOS is the maximum ACOS you can run on attributed ad sales and still not lose money on those orders.

You calculate it from contribution margin, not from “what feels reasonable.” At a SKU level, your contribution margin rate is:

Contribution margin rate = (Selling price - Amazon fees - COGS - prep/inbound - other per-unit costs) / Selling price

Your break-even ACOS is roughly that same percentage. If your contribution margin rate is 32%, your break-even ACOS is about 32%. Above that, you are paying more in ads than the per-order profit can support.

Two practical wrinkles:

First, refunds and returns lower your realized margin. If returns are meaningful in your category, reduce your break-even ACOS to create a buffer.

Second, discounts change everything. Coupons and price cuts reduce revenue, but many fees and COGS do not fall proportionally. If you run promotions, you need break-even ACOS targets for “full price” and “promo price,” or you will chase an ACOS number that is mathematically impossible to make profitable.

The minimum viable profit tracking setup (no overengineering)

If you try to track every possible variable from day one, you will stall. The goal is to get accurate enough to make bid and budget decisions that protect profit.

Start with three layers: SKU economics, PPC performance, and a clean mapping between them.

1) Lock down SKU economics you can trust

For each parent/child you advertise, you need a current estimate of:

Selling price (and promo price if relevant), landed COGS, FBA fees, and any per-unit costs you always pay (prep, labeling, inserts, etc.). Keep this in a single source of truth and update it when costs change. Freight increases and fee changes are not “background noise.” They directly shift your break-even ACOS.

If you are using blended COGS across variations, be honest about the trade-off. Blended numbers are faster, but you may end up over-scaling an unprofitable variation because the parent looks fine.

2) Choose the right PPC attribution window for decisions

Amazon reports 7-day, 14-day, and 30-day attribution (depending on ad type and reporting view). Short windows react faster but undercount longer-consideration purchases. Longer windows smooth volatility but hide problems.

For most operators, the best compromise is: use a shorter window (like 7 days) to control bids and budgets weekly, and use a longer window (like 14 or 30) to validate whether the strategy is paying off.

If your product has repeat purchase behavior, you also need to accept that Ads Console will not credit future repurchases. That does not mean ads are unprofitable. It means you should set different expectations for new-to-brand acquisition versus harvest campaigns.

3) Map spend and sales to the SKU level

Profit tracking breaks when spend is aggregated at a campaign level while margin differs by SKU. You want to know profitability per advertised ASIN, not just per campaign.

If you run Sponsored Products with one SKU per ad group, mapping is clean. If you use multi-ASIN ad groups (common in “catch-all” structures), you will struggle to assign profitability correctly.

This is why structure is a profit lever, not just an organizational preference. Cleaner structure gives you cleaner profit signals, which lets you be more aggressive where it is justified.

The profit metric that drives real decisions

Once you have break-even ACOS, you can stop debating “good ACOS” and start making decisions based on profit per click and profit per dollar spent.

A simple, operator-friendly metric is contribution profit after ads:

Profit after ads = Ad sales x contribution margin rate - ad spend

Run that at the SKU level over a defined window and you get a number you can act on.

If it is positive and stable, you can scale budget and bids (within inventory constraints). If it is negative, you need a clear playbook: reduce bids, tighten targeting, add negatives, adjust placements, or change the offer.

Where it gets nuanced is when a SKU is negative on ad-attributed profit but clearly drives organic lift. That is real - but you should prove it with a controlled view (see below) instead of assuming every loss is “ranking investment.”

Account for organic halo without lying to yourself

Amazon PPC can generate organic sales by improving rank, conversion rate, and brand visibility. That halo is often the difference between “barely works” and “scales hard.”

The mistake is treating halo as a blanket excuse. The fix is to measure it in a disciplined way.

Pick a SKU, choose a stable baseline period, then compare total sales and ad spend after you scale PPC. If total sales rise more than ad-attributed sales, the difference is your halo estimate.

You can do this by looking at:

Total ordered revenue (Business Reports) versus ad-attributed sales (Ads Console) for the same period. It is not perfect, but it is directionally useful.

If you are scaling spend and total sales stay flat while ACOS worsens, you are not buying halo. You are buying expensive clicks.

If total sales increase and your blended ACOS (spend divided by total sales) stays within your margin limits, you can justify higher ad ACOS on that SKU.

Operational rules: how profit tracking changes your optimizations

Profit tracking is only valuable if it changes what you do Monday morning.

Here are the decisions it should drive.

Bid changes: stop optimizing for ACOS alone

If a target is above break-even ACOS but has strong conversion and high click volume, that usually signals a bid problem or a placement problem - not a keyword problem. Lower bids, reduce Top of Search multipliers, or restrict to exact match if you are bleeding on broad.

If a target is below break-even ACOS and has room to scale, raise bids gradually and watch CPC sensitivity. Many accounts underbid profitable terms because they are trained to fear ACOS spikes. Profit tracking gives you permission to win more auctions when the math supports it.

Keyword harvesting and negatives: profit-first filtering

Not every converting term deserves to stay. A keyword that converts at a low rate can still be profitable if CPC is low and AOV is high. A keyword that converts well can still be unprofitable if it only sells during coupon periods and your margins collapse.

Your harvesting rule should be: promote terms that are profitable or clearly trending toward profitability as they gather data, and negate terms that are persistently unprofitable after a reasonable click threshold.

Budget pacing: allocate spend like a portfolio

Budgets should follow profit opportunity, not habit.

A SKU with positive profit after ads and stable inventory deserves budget priority. A SKU that is negative but strategically important (launch, seasonal, rank defense) should have a capped “investment budget” with a time limit.

If you cannot explain why a SKU is allowed to lose money, it should not be allowed to lose money.

Common traps that destroy Amazon PPC profit tracking

The first trap is using outdated costs. One supplier increase can turn a previously “safe” ACOS target into a loss.

The second is mixing objectives inside one campaign. If your launch terms and your harvest terms share budgets and placements, the profit signal gets muddy and you end up underfeeding the winners.

The third is ignoring time. Profit can look bad in a 7-day view during a price test, and look great in a 30-day view after the test ends. Pick a decision window and stick to it, then use a second window for validation.

The fourth is assuming automation equals strategy. Automation is a force multiplier, but only if it is optimizing toward the right goal and the right unit economics.

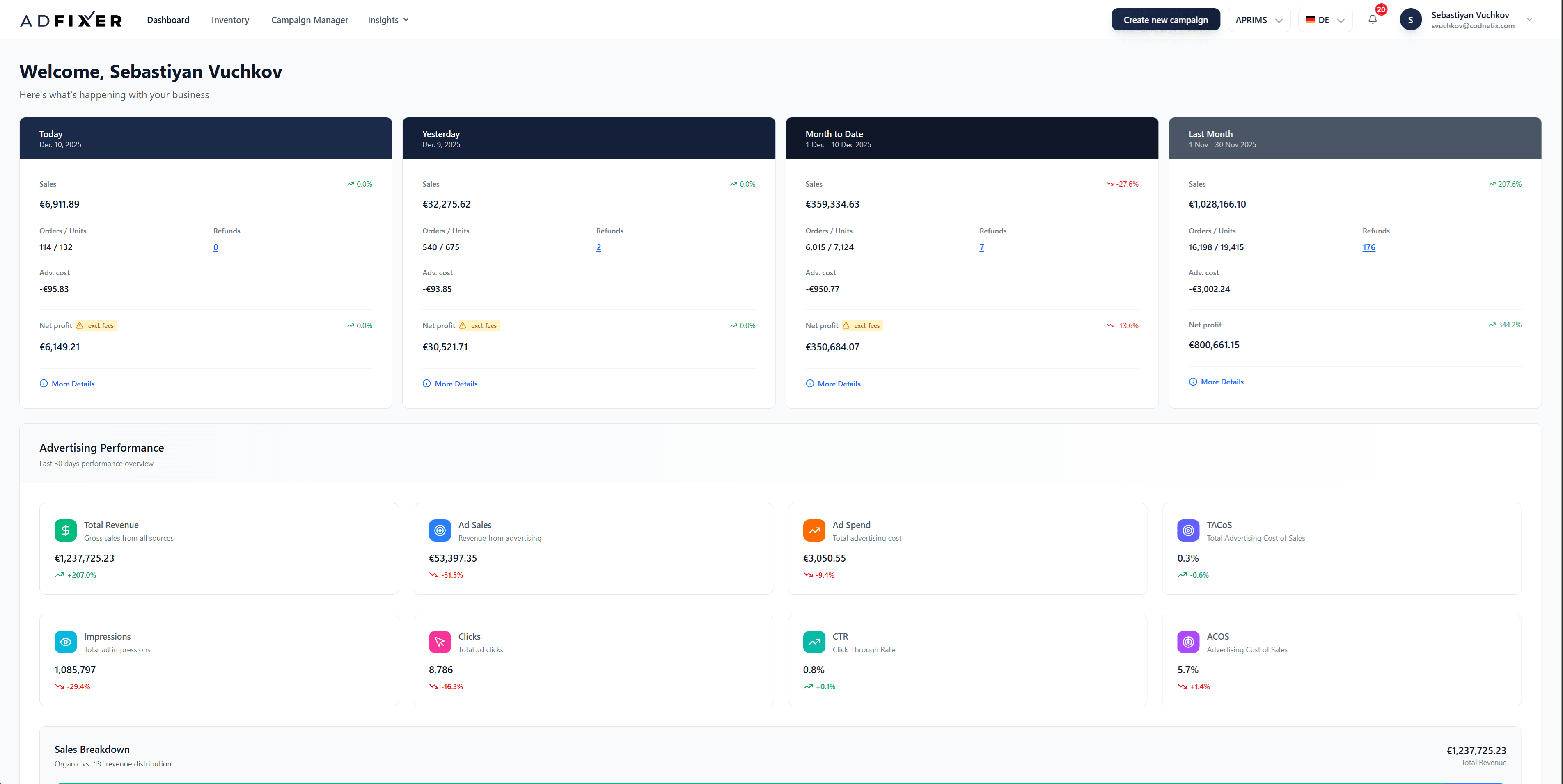

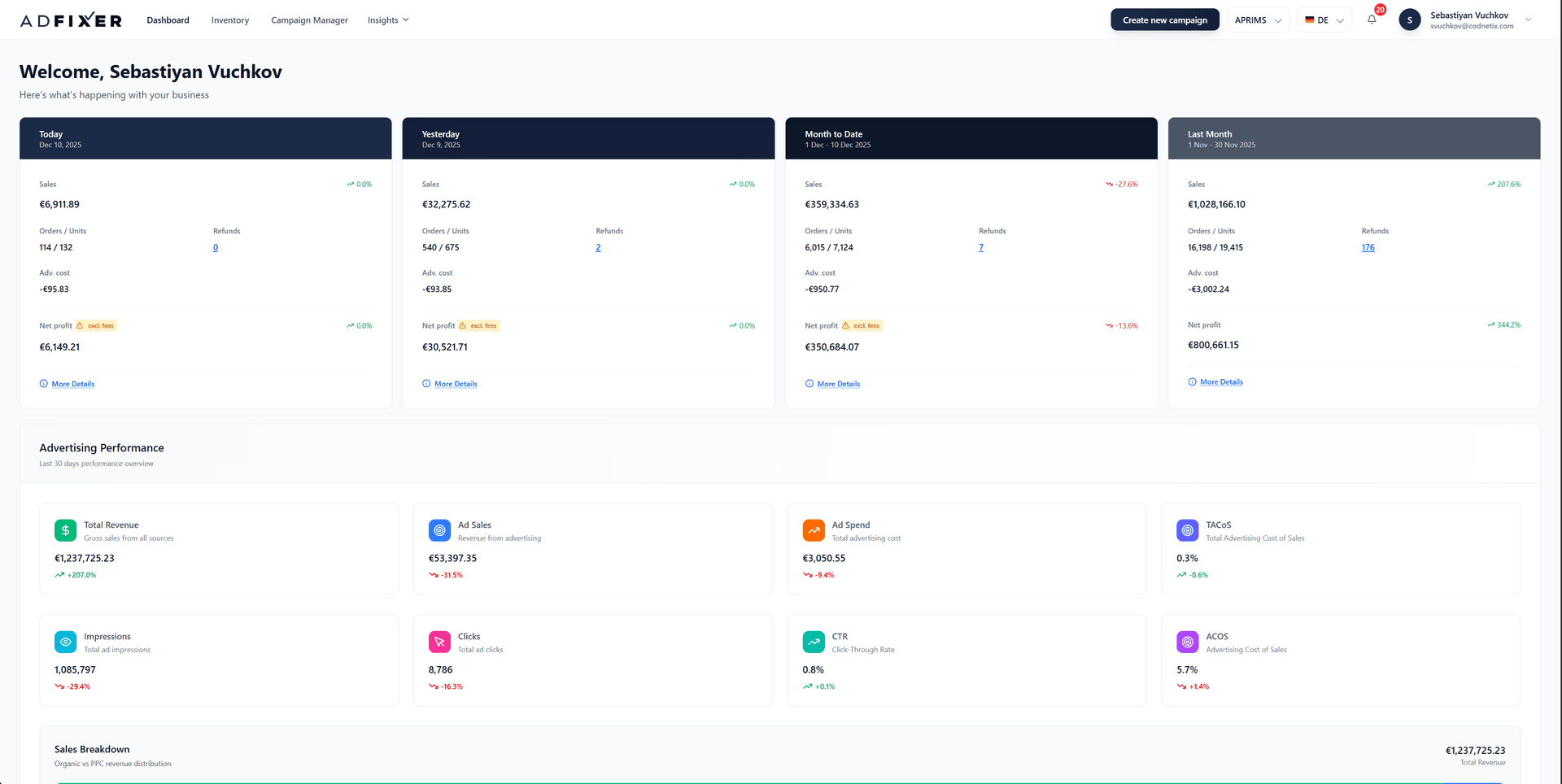

If you want always-on optimization toward a target ACOS/ROAS with profit visibility in the same workflow, that is exactly what AdFixer is built around - hourly bid changes, negative automation, day-parting, and a dashboard that keeps spend tied to outcomes you can defend.

A simple weekly profit tracking cadence that scales

Profit tracking should not become a reporting project. It should be a cadence that protects margin while you scale.

Once a week, review SKU-level profit after ads on a short attribution window. Make bid, placement, and negative decisions to correct clear losers and feed clear winners.

Every two to four weeks, validate against a longer window and check blended performance versus total sales to estimate halo. If the halo is real, you can afford to push harder. If it is not, tighten back to break-even targets.

Monthly, refresh your costs and fees so your break-even ACOS stays honest. This single habit prevents “mystery” profit compression.

Closing thought: the fastest way to grow on Amazon is not chasing the lowest ACOS - it is building a system where every extra dollar of spend has to earn its place in your margin.